For 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have reported the following total numbers of deaths related to firearms use1:

Unintentional: 505

Suicide: 21,175

Homicide: 11,208

Undetermined (intent not clear): 281

Legal intervention/war (generally, police intervention): 467

Total deaths related to firearms use: 33,636

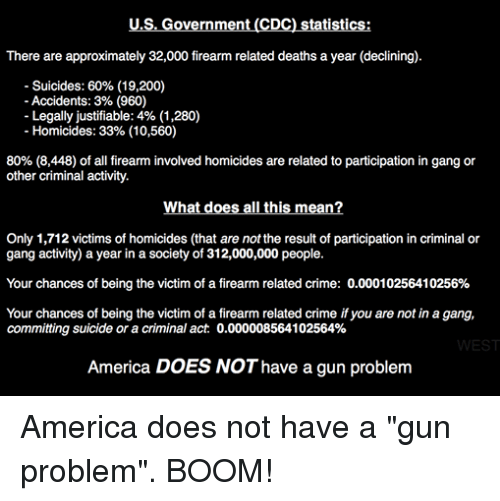

While the total number of deaths related to firearms use in 2014 was 33,636, many firearms rights proponents argue that suicide should not be counted among that number. An example of a meme suggesting this follows:

The meme has several problems (click here for that discussion) but for the purpose of this page, we’re just going to focus on the dismissal of firearms-facilitated suicide as a problem. Most often, the reasoning behind such a move is a declaration that, “People who are going to kill themselves will just choose some other way if they don’t have a gun.” In injury prevention terms, we call this “means substitution”; in other words, if you lose access to one means of injury, you end up getting injured using another means. The available data suggests this simply isn’t true.

Stepping back from firearms for a moment, it’s helpful to get a better overview of suicide as a whole. Suicide was the 10th leading cause of death in our country overall in 2014*, a stable statistic, and ranks quite a bit higher among younger folks who aren’t succumbing quite so much to things such as cancer, stroke, and heart disease; in fact, it’s the second leading cause of death from ages 10-34, and the fourth leading cause of death from ages 35-54.2 From age 15 up, firearms are the most commonly used method of suicide (the 10-14 year olds go with suffocation – mostly hanging – which beat out firearms 225 to 174 in 2014). The total number of US suicides in 2013 was 41,149.3

Based simply on the numbers above, suicide is clearly a problem in the United States. Bolstering this, the World Health Organization estimates that there are roughly 10-20 suicide attempts for every completed suicide worldwide.4 Stating that something that negatively affects this many people in our country isn’t a problem is just asinine.

Looking at suicide in more detail, the available evidence shows that it is, by and large, an impulsive act. A 2010 study from France, looking at 1,009 patients who attempted (but survived) at least one suicide attempt, divided the patients into three clusters for analysis: impulse-ambivalent, well-planned, and frequent attempters. The impulsive-ambivalent group was by far the most prevalent (604 members vs 365 and 40 for the others, respectively). The well-planned group made more preparations for their suicide attempts, took more precautions to avoid interruption or rescue, and generally used more lethal means than the impulse-ambivalent group. Several other studies, such as this one (with links to several more), support the concept that the majority of people attempting suicide do so impulsively.5

Empirical observation bears this out, and takes us back to a more direct discussion of means substitution. Many articles, going back decades, describe observations of suicide rates during “natural experiments”; in other words, a potentially important variable was changed for purposes other than research, and researchers used the opportunity to study the effects of that change. In Japan, domestic gas (i.e., gas used to heat homes, ovens, etc.) was a popular means to commit suicide. As the gas was detoxified over a long period, the suicide rate decreased, with no increase in the use of other methods.6 In New Zealand, a remarkable study looked at a popular suicide bridge on which suicide barriers had been placed in 1937.7 For various reasons, the barriers were removed in 1996. Several suicides later, the barriers were replaced with an improved design in 2003. Looking at the number of suicides in the years immediately prior to barrier removal, the time in which the barriers were not in place, and the years immediately after barrier replacement, the authors found:

1991-1995 (old barriers): 5 suicides, 1 per year

1997-2002 (no barriers): 19 suicides, 3.17 per year

2003-2006 (new barriers): no suicides

It’s important to understand that to be effective in reducing suicide, means restriction has to focus on methods of suicide that are highly lethal.8 Reducing access to pillows is not likely to lead to a significant decrease in deaths from pillow suffocation. A surprising number of prescribed and over-the-counter medications – which, for the sake of public health, I won’t be listing here – don’t have significant toxicities even when consumed in large quantities. Rather, means restriction for suicide prevention focuses on those means with high likelihood of killing a person when used.

How does this relate to firearms? It is clear from the discussion above that suicide is often an impulsive act, and that access to methods of suicide with high case fatality rates during times of impulsive behavior leads to a higher suicide completion rate. It stands to reason that if impulsively suicidal people have less access to firearms during their brief period of suicidality, they are less likely to kill themselves. As it turns out, most of the literature that’s available supports this hypothesis. Some compare suicide rates in US states with more-restrictive gun laws vs those with less-restrictive gun laws, and conclude that states with more-restrictive gun laws have lower suicide rates.9, 10 Others show similar associations at a national level. 11, 12

In fairness, some literature does support that means substitution does occur. However, the substituted means are generally less lethal, and the substitution rate is far less than 100%; that is, many people who lose the opportunity to kill themselves with the first means don’t end up going further, choosing a second means, and attempting again.13, 14

In summary, there are a few things that are clear:

- Firearms are used in the majority of suicides.

- Suicide is a major problem in the United States, as a leading cause of death among all ages but especially so among younger persons with more years of potential life lost.

- Suicides are often an impulsive act.

- Many people who attempt suicide regret their decision, and if they survive, do not attempt suicide again.

- Restricting access to highly lethal means with which to attempt suicide can be one effective component of a program to meaningfully reduce the rate of completed suicide.

- Means restriction does not necessarily result in means substitution.

- Where means substitution does occur in the context of suicide, it is generally incomplete; that is, many people give up on the suicide attempt entirely, rather than trying a different means.

- Means substitution to a less-lethal means, with a similar or smaller number of people attempting suicide via the new means, will result in a lower suicide completion rate.

Given all that, it’s safe to say that we shouldn’t ignore suicide when it comes to discussions of public health, public policy, and firearms.

* 2014 data are available for “leading cause of death” charts, but the final data reported for 2013 are the latest available for more detailed reports as of July 2016. Data referenced on this page are the latest available at this time, but are a combination of 2013 and 2014 data.

References

- http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_02.pdf

- http://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_age_group_2014_1050w760h.gif

- http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.pdf

- Hoven CW, Mandell DJ, Bertolote JM. Prevention of mental ill-health and suicide: public health perspectives. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(5):252–256.

- Gvion Y, Apter A. Aggression, Impulsivity, and Suicide Behavior: A Review of the Literature, Archives of Suicide Research. 2011;15(2):93-112.

- Lester D, Abe K. The effect of restricting access to lethal methods for suicide: a study of suicide by domestic gas in Japan. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989 Aug;80(2):180-2.

- Beautrais AL, Gibb SJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Larkin GL. Removing bridge barriers stimulates suicides: an unfortunate natural experiment. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009 Jun;43(6):495-7.

- Yip PS, Caine E, Yousuf S, Chang SS, Wu KC, Chen YY. Means restriction for suicide prevention. Lancet. 2012 Jun 23;379(9834):2393-9.

- Rodriguez Andres A, Hempstead K . Gun control and suicide: the impact of state firearm regulations in the United States, 1995–2004. Health Policy 2011 Jun;101(1):95–103

- Conner KR, Zhong Y. State firearm laws and rates of suicide in men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2003 Nov;25(4):320-4.

- Kapusta ND, Etzersdorfer E, Krall C, Sonneck G. Firearm legislation reform in the European Union: impact on firearm availability, firearm suicide and homicide rates in Austria. Br J Psychiatry. 2007 Sep;191:253-7.

- Chapman S, Alpers P, Agho K, Jones M. Australia’s 1996 gun law reforms: faster falls in firearm deaths, firearm suicides, and a decade without mass shootings. Inj Prev. 2006 Dec;12(6):365-72.

- Sarchiapone M, Mandelli L, Iosue M, Andrisano C, Roy A. Controlling access to suicide means. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011 Dec;8(12):4550-62.

- Daigle MS. Suicide prevention through means restriction: assessing the risk of substitution. A critical review and synthesis. Accid Anal Prev. 2005 Jul;37(4):625-32.