Comparing Firearms and Vehicles

When people discuss regulating firearms, a common retort is that we should regulate other deadly things (see physicians and drunk drivers for other examples). Vehicles, being involved in the deaths of somewhere over 30,000 people on public US roadways each year, are a frequent target for this type of meme, perhaps because somewhere over 30,000 people die in the US each year as a consequence of firearm-induced injury. (As a note, the 9,000 figure quoted above excludes suicides, which is inappropriate from an injury prevention standpoint.)

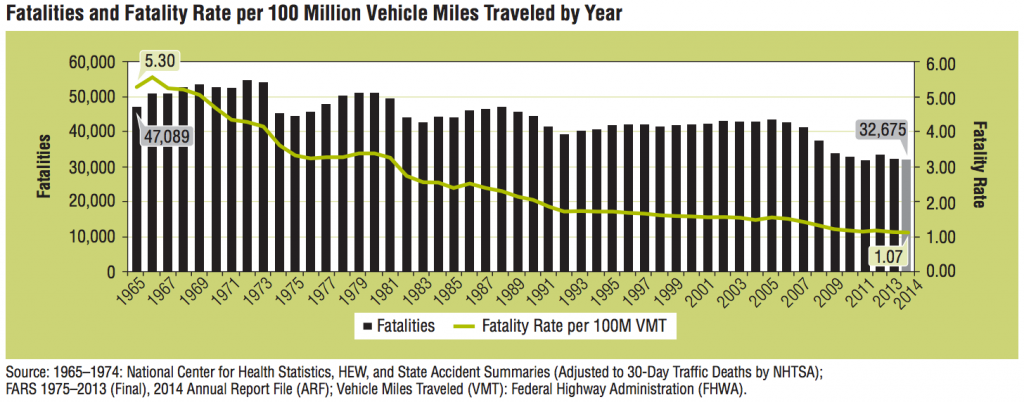

As it turns out, motor vehicle collision (MVC) deaths are much less frequent than they used to be. Reviewing data made available each year from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), we can see that the overall trend for MVC deaths is improving; in fact, from 2006 to now, with a small twitch of positive signal in 2012, the death rate has dropped each year. 1 (Remember that a rate involves the amount of something per amount of something else, which accounts for different exposure risks. In this case, it’s calculated as fatalities per 100 million vehicle miles traveled.)

How did this happen?

In injury prevention, we often talk about the “4 Es”:

- Education – making sure people know about the problem

- Enforcement/Enactment – legislation that provides penalties for making the problem worse

- Engineering – developing and implementing technology to decrease the likelihood/severity of injury

- Economics – providing penalties or incentives to encourage more healthful behaviors

We’ve used all four of these when it comes to motor vehicle safety, and it’s a tried and true approach to other injury prevention models as well. Each of those four pillars has some advantage over the other, and it would be foolish to ignore any of them if you’re trying to achieve maximal injury prevention and mitigation.

So, where does that leave us with the meme above? It’s difficult to directly compare MVC fatalities to firearms-related deaths for a few reasons, most notably that we don’t have good denominator data that we can use to determine a rate for firearms-related deaths. Knowing the total number of guns in the US wouldn’t do it, any more than knowing the total number of cars would; if they’re not out of the locked garage or locked safe, they’re probably not contributing to the injury risk. For cars, we can use vehicle miles traveled as the denominator (good estimates on this are available from a compilation of sources and techniques that NHTSA has developed), but what do we use for guns? There’s really not a good answer that we can track. Ideally, it would be a measure of how frequently guns are carried and for how long, but that’s just not possible to determine.

That stated, we do know that with lots of patience, effort, and money, we’ve been able to make a sizable difference in the number of people killed on our public roadways since we really started to work on it in 1966 (the year a seminal publication called “Accidental Death and Disability: the Neglected Disease of Modern Society” was published).2 Maybe following that model with firearms is a reasonable comparison after all.

References

1: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/812246.pdf

2: http://www.nap.edu/read/9978/chapter/1